Wrapping != Abstraction

This is a sequel to Build and Scale Platform Product and Enterprise Platform Strategy.

⚠️ Warning: Theoretical discussion ahead.

One aspect I haven’t touched on so far regarding building a Platform Product is abstraction.

You’ve probably heard every day about how abstraction reduces cognitive load1, improves user experience, and allows developers to focus on writing their code instead of worrying about infrastructure2. You hear it so often that it almost automatically triggers a yawn.

Buzzwords such as “Internal Developer Platform” are built on top of the idea of abstraction, if not entirely.

But, what are we talking about when we talking abstraction?

Let’s start from the basics.

Interface

An interface defines the protocols for communication with a component or service. It can be a virtual method in C++, an interface in Golang, traits in Rust, but most commonly, it’s the API of a service. It defines not only what operations it supports but also the order in which the methods/api should be called. For example, A socket is an interface implementing byte-oriented communication between two endpoints.

Layer Architecture

Layer architecture can involves building higher level constructs and concepts over lower level ones. This pattern is best manifested in operating systems, such as file system is built on top of storage system; HTTP on top of socket and libraries on top of system calls.

Layered architecture doesn’t necessarily mean a rise in the level of abstraction. It can also involve different layers responsible for distinct responsibilities, with higher layers utilizing lower ones, as exemplified by the typical 3-tier web application.

Layers can be open or closed. Closed layer can’t be walked around, while open layers can. We will come back to this disctintine later.

Control Plane and Data Plane

The terminology of control plane and data plane comes from routers. The control plane is responsible for controlling how the packets are routed and the data plane is responsible for the actual routing.

This architecture is prevalent in modern cloud and cloud-native software. Calico, service mesh, Kubernetes, and the whole AWS cloud have such structures.

In Calico, the control plane is responsible for hosting the network policy and distributing it to the data plane, in which each node will set the iptables properly.

In Istio, the control plane is responsible for hosting various configurations and distributing the Envoy configuration to the Envoy proxy running in each pod.

Kubernetes is a bit more complex since inside the control plane there are more controllers each responsible for certain aspects of the whole configuration, e.g., the scheduler is responsible for taking the pod request and scheduling it to the right node, where kubelet will be responsible for pulling the image and running the containers.

It is the same for all AWS services. For example, you start an EC2 through the API (control plane), and after that the EC2 will running without relying on the control plane (something called static stability).

When talking about abstraction and wrapper below, we normally means do it for control plane API.

Abstraction

Talking about abstraction risks ending up too abstract.

Abstraction can mean either interface or layered architecture. The former is abstraction at the component level, the latter at the system level.

Abstraction is difficult. The right abstraction requires a thorough understanding of the domain, and such understanding takes years. Good abstraction is not necessarily simple, since the domain it models may be inherently complex. Kubenetes is such example since it is abstraction all the things related to scalable and secure application deployment. On the other hand, a complex system can be abstract in seeming unbelivable simple interface, such as the ioctl.

Without thorough understanding of the domain, a generic abstraction can be insufficient or overly complicated. Kubernetes Ingress is considered to be former case. So folks developed the Gateway API later to fix it. C++ can be considered later, as too much is required to get things done properly.

Wrapper

Unlike abstraction, a wrapper won’t create a cohesive higher-level concept or construct over the things it wraps.

For example, Helm templating is a wrapper rather than an abstraction, while the Golang channel is both a wrapper and an abstraction over the message queue and mutex. The former exposes only the parameters users need to configure and wraps them with some defaults; the latter creates a new construct that is part of the Golang concurrent programming model.

Similar to build the right abstraction, creating the right wrapper is equally hard. It requires an understanding of the existing interface of the domain it’s trying to wrap, as well as the specific use case it’s trying to serve. Wrappers often make assumptions and prioritize certain use cases that are a subset of the use cases the original interface can support. The goal is to make those high-priority use cases easier, and, in lost of times, the consequence is making other use cases harder, if not impossible. One option is make the wrap open layer but that come with the consequence of end up support two layers.

In addition, if the underlying domain keeps changing, as it is often the case for cloud and cloud native software, the burden and deficiencies of the wrapper become exacerbated. It either breaks or fails to catch up, becoming the bottleneck of the user and the underlying domain it mediates. In another word, you not only need to build the wrapper but also operate the wrapper. Remember:

The cost to build a system, service, or application is nothing compared to the cost of operating it3.

However, if you understand the domain, the user, and have the capability to build and are prepared to operate it, by all means build that wrapper.

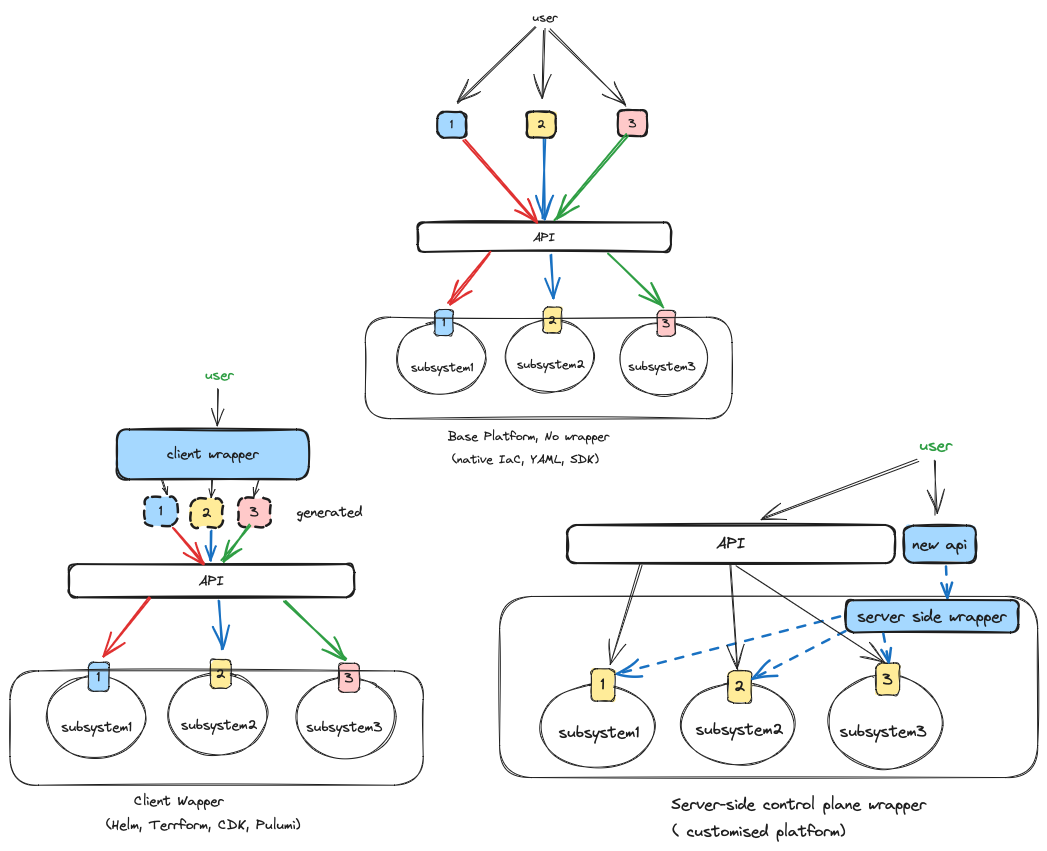

Client and Server Wrapper

Services are often exposed through HTTP API, through which client will talk to. It is the boring client-server architecture.

What I want to call to attention is the distintiion between client wrappers and server wrappers.

Instead of writing code to communicate with the service, it became increasingly popular and even dominant, especially in cloud resource provisioning, for clients to interact with services by applying a configuration file. Examples are kubectl apply and terraform apply. Helm and Terraform are tools to make client-side composition easier. Those tools are the choice of so called DevOps engineers. Application developers want single language rules for both application code and infrastructure code. CDK and Pulumi are choices for those users. More advanced users can go straight to the SDKs. Just realized this is a short overview of the landscape of infrastructure as code.

In comparison, there is not so much tools specific designed implement server-side wrappers. There are only patterns and specifci solution in specfic ecosystems. Facade is a design patten that exposes a simpler interface over a bunch of complex subsystems. In Kubernetes, server-side wrapping can be accomplished using Custom Resource Definitions (CRDs) with custom controllers, or by utilizing the composition feature of Crossplane.

Orchestration

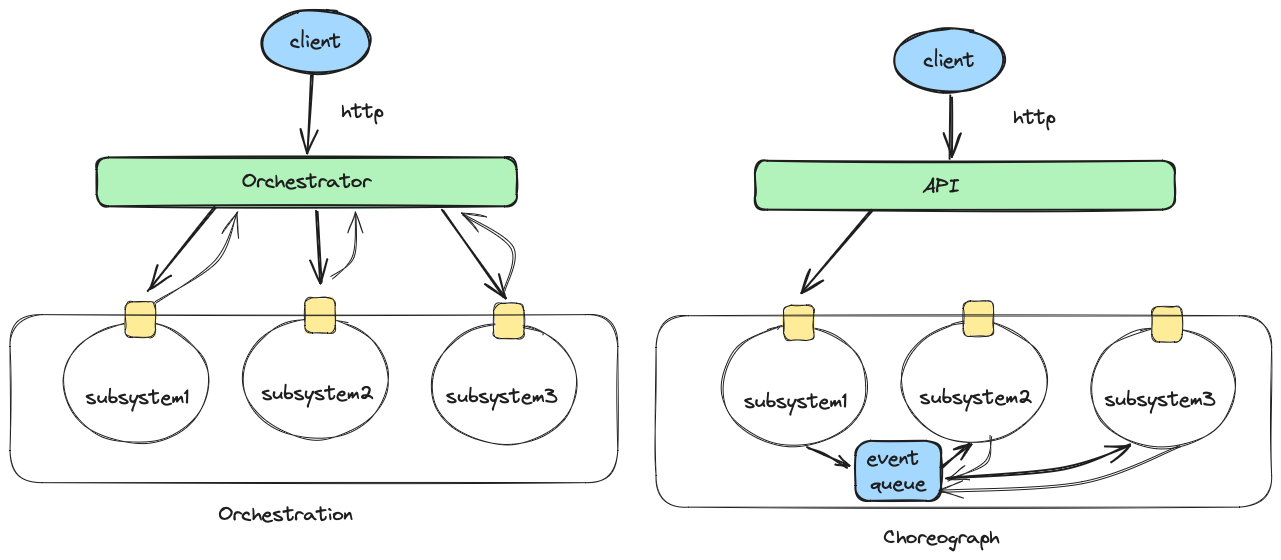

A wrapper is normally thin, like the wrapper on a Christmas gift box. When there is a lot of logic and coordination required across multiple services, one pattern is orchestration.

I also like to differentiate between two types of orchestrators: client and server-side orchestration. A server orchestrator sits in front of all the services it coordinates. Incoming requests will flow through the orchestrator, which is responsible for calling the individual services in the designed flow. This is what the normal orchestration pattern refers to.

The action you performed in the CI pipeline is a great example of client-side orchestration. After you push your code, your CI pipeline will build the code, scan it, test it, containerize it, push it to the registry, and maybe trigger another workflow to deploy it. This requires quite a lot of coordination.

Server-side orchestration suffers from the same downsides as a wrapper or any centralized point does. An alternative pattern is choreography, decentralizing the control to each service, normally through an event-driven mechanism. When you’re deploying an application to Kubernetes, behind the scenes4, there are multiple services working collaboratively together. The deployment request will be persisted to the data store. The scheduler will pick that up and figure out where to place the pods and save the decision in a datastore. The agents on the corresponding nodes will notice that and start pulling the image and running the containers.

Summary

When trying to build a wrapper on a standard base platform, first, ask three questions:

- Are we talking about abstraction, wrappers, or orchestrators? Will it on the client or server side?

- How much do we know about the domain and the users?

- How are we going to operate it at scale?

Then, forget all nonsense you read here. Just build something.

-

Every time I hear the word “cognitive load,” I need to pause and wonder why not a simpler word was used to reduce my cognitive load. I concluded that it is the type of word that makes you sound smart. ↩

-

Heroku is often mentioned as the holy grail of app deployment. Ironically, i’m not quite sure of Heroku’s significance nowadays. ↩

-

https://www.allthingsdistributed.com/2024/06/introducing-distill-cli.html ↩

-

From the client perspective, it’s hard to tell which pattern is used behind the scenes. Such distinction may be not necessary or even pedantic. Kubernetes is called an orchestration platform, but there is not a single orchestrator in it. ↩